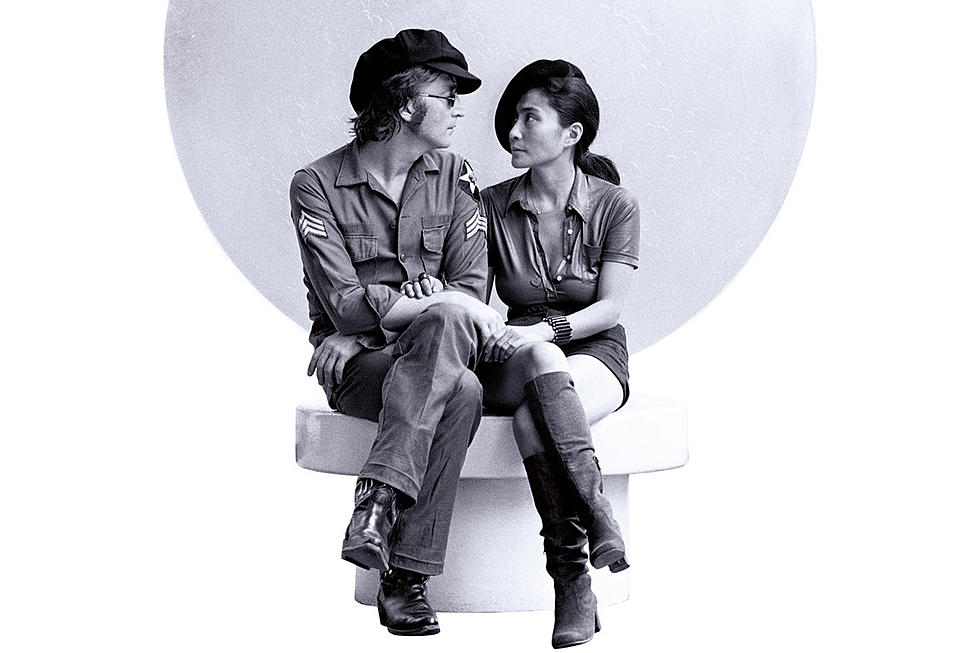

How John Lennon Told the Story of His Love for Yoko Ono in Song

John Lennon began chronicling his love for Yoko Ono in the late '60s, and that narrative continued through a posthumous album released years after his murder.

In the end, these songs would account for half of Lennon's four U.K. chart toppers – beginning with the Beatles' "Ballad of John and Yoko." Recorded during an April 14, 1969 session with Paul McCartney, the single took fans into the flurry of activity surrounding their nuptials – including their difficulties, because of residency requirements, in finding a venue.

"It was very romantic. It's all in the song, 'The Ballad of John and Yoko,'" Lennon told Rolling Stone in 1970. "If you want to know how it happened, it's in there."

The track then points fans to the next major event in their shared lives: A bed-in for peace, which began on March 25, 1969 in the presidential suite at the Hilton Hotel in Amsterdam. Certain that the press would swarm around the news of his marriage, Lennon and Yoko decided to leverage the coverage to discuss their opposition to the continuing Vietnam conflict.

"The newspapers said, 'Say, what're you doing in bed?'" Lennon sang on "The Ballad of John and Yoko." "I said, 'We're only trying to get us some peace.'"

Many assumed that they would engage in some sort of public display of affection, Lennon argued at the time. After all, Lennon and Ono had already released an album of found sounds with a cover that found the pair completely nude.

They filmed everything in Amsterdam; recordings from the week-long event were also included on Side 1 of The Wedding Album, their third similarly experimental project together.

Listen the Beatles Perform 'Ballad of John and Yoko'

"The Ballad of John and Yoko" arrived a couple of months later, on May 30, 1969. In less than a year, Paul McCartney had announced the Beatles' split, via a Q&A that arrived with his 1970 debut. The band's final released studio effort arrived in May 1970, followed by Lennon's first proper solo album that December.

Some were actively blaming Ono for the Beatles' breakup, and she's specifically mentioned in two of the most telling moments from 1970's Plastic Ono Band: "Hold On" was an encouraging ballad aimed at a couple who feel beset on all sides. Meanwhile, the hard-eyed "God" made clear Lennon's intention to move on from many of the things he once placed his faith in – including his old group: "I just believe in me," Lennon sang. "Yoko and me."

Elsewhere, the delicately conveyed "Love" spoke in the simplest of terms about his feelings: "Love is you, you and me. Love is knowing, we can be." But "God" laid everything bare.

"I was going to leave a gap and say, just fill in your own, for whoever you don't believe in," Lennon told Rolling Stone in 1970. "It just got out of hand. But Beatles was the final thing because it's like I no longer believe in myth, and Beatles is another myth. I don't believe in it. The dream's over. I'm not just talking about the Beatles is over, I'm talking about the generation thing. The dream's over, and I have personally got to get down to so-called reality."

Released on Sept. 9, 1971, Lennon's follow-up album Imagine included a gentle paean to wedded bliss, a song that again specifically referenced his wife, and another that spoke to the difficulties he continued to experience in a committed relationship.

"Jealous Guy" grew out of a White Album-era Beatles track called "Child of Nature." "The lyrics explain themselves clearly," Lennon told Rolling Stone in 1980. "I was a very jealous, possessive guy – toward everything. A very insecure male. A guy who wants to put his woman in a little box, lock her up, and just bring her out when he feels like playing with her."

"Oh My Love" spoke to the way Lennon's new relationship opened his heart to life's smallest joys. Imagine then closes with the stripped-down "Oh Yoko," a song that couches an almost obsessive co-dependency with this celebratory vibe. For Lennon, love could – and, in fact, seemed to often be – a combination of very disparate things.

Listen to John Lennon Perform 'Jealous Guy'

Lennon and Ono hit a rocky patch in the run up to Mind Games. That's the subtext of "Out the Blue," which recounted their partnership's beginnings with no small amount of nostalgia. "Aisumasen (I'm Sorry)" underlines their troubles even more clearly. This was Lennon's attempt, in broken Japanese, to apologize for some unnamed slight – and its abrupt ending seemed to indicate that his pleas for forgiveness were rejected. In fact, Lennon and Ono had split by the time the album arrived on Oct. 29, 1973.

Lennon then began his so-called "lost weekend," an 18-month sojourn into drunken grief that included the Sept. 26, 1974 release of Walls and Bridges. He attempted to soldier on with "Going Down on Love," the opening track. "When the real thing goes wrong," Lennon sang, "and you can't get it on, and your love she has gone – you got to carry on."

It was all a front. "I think I was suicidal on some kind of subconscious level," Lennon told the Los Angeles Times in 1980. "The goal was to obliterate the mind so that I wouldn't be conscious. I didn't want to see or feel anything. Part of me can't believe I would self-destruct — the youthful part that feels invincible. Yet another part realizes that I could have died."

Elsewhere, Lennon used "What You Got" to beat himself up for going astray, while "Bless You" – with its heartbreaking phrase "where ever you are" – found Lennon plaintively calling out to Ono. "Some people say it's over, now that we spread our wings," he sang. "But we know better, darling."

They did, in fact, get back together in 1975 – and, when Ono became pregnant, Lennon promptly retired from music.

"Making music was no longer a joy," he told the Los Angeles Times. "For 20 years, I had been under this pressure to produce, produce, produce. My head was cluttered. Every time I'd sit down to write, there would be a cloud between me and the source, a cloud that hadn't been there before. I was trapped and saw no way out."

During the ensuing break, which ended up spanning five years, Lennon switched roles with Ono: She managed the business side of things, and he served as a doting "house-husband" with their son Sean. His eventual comeback album Double Fantasy – in particular on "Watching the Wheels" and "Cleanup Time" reflected this shift toward domesticity, but also a maturing sensibility toward his marriage.

Listen to John Lennon Perform 'Grow Old Along With Me'

"(Just Like) Starting Over" celebrated the sense of renewal that surrounded the era, while "I'm Losing You" once again confessed to his penchant for an acute neediness. "Woman" took a more universal perspective, while focusing on how thankful Lennon remained to have been taken back.

"'Woman' came about because, one sunny afternoon in Bermuda, it suddenly hit me," Lennon told Playboy in 1980. "I saw what women do for us. Not just what my Yoko does for me, although I was thinking in those personal terms. Women really are the other half of the sky, as I whisper at the beginning of the song. And it just sort of hit me like a flood, and it came out like that."

"Dear Yoko" used a Buddy Holly-esque approach to describe how integral Ono had become to him by the end: "Even when I watch TV, there's a hole where you're supposed to be." In an echo of the Imagine album, this Yoko-titled paean to his spouse also closes out Lennon's portion of Double Fantasy, which arrived in November 1980 – just weeks before a deranged fan killed Lennon on Dec. 8, 1980.

"Grow Old Along With Me," also written during that summer vacation in Bermuda, was based on a poem by Robert Browning. Ono had challenged Lennon to write the song after she used a sonnet by the poet's wife Elizabeth Barrett Browning as inspiration for "Let Me Count the Ways." Lennon demoed the song, but never finished it.

"For John, 'Grow Old With Me' was one that would be a standard, the kind that they would play in church every time a couple gets married," Ono later remembered. "It was horns and symphony time. But we were working against deadline for the Christmas release of the album, kept holding 'Grow Old With Me' to the end, and finally decided it was better to leave the song for Milk and Honey, so we won't do a rush job."

The posthumous Milk and Honey arrived on Jan. 9, 1984, and by then the message embedded in "Grow Old Along With Me" had undergone a radical shift. Instead of looking ahead to a sweetly romantic future, it felt like a devastatingly sad message of lost devotion.

Ono later commissioned Beatles producer George Martin to write an orchestral score for the song, fulfilling her husband's wishes. The embellished new track, which featured Martin's son Giles on bass, initially appeared on Nov. 2, 1998 as part of the John Lennon Anthology box set.

Beatles Solo Albums Ranked

See John Lennon in Rock’s Craziest Conspiracy Theories

More From KYBB-FM / B102.7