How Talking Heads Turned a Corner on ‘Fear of Music’

Talking Heads' Fear of Music found their always-offbeat observations set to turbulent, often strikingly ominous music beds that grew out of loose, but ultimately uncredited full-band jams. As such, it wasn't a departure so much as a deepening and a dimming of what came before.

It's clear now, though, that the ominous and intriguing Fear of Music was a bellwether juncture for the band, its music and its future.

They were pushing, and hard, against the edges of an approach that always seemed to include a wink and a nudge in the past. As the ties that bound the band began to weaken, however, their approach reflected the looming clouds all around. You hear it in the fin de siecle dread surrounding their radio favorite "Life During Wartime" and the disturbingly beautiful nihilism of "Heaven."

The album's explosive opener "I Zimbra," which featured African cadences, a memorable guest turn by King Crimson's Robert Fripp and lyrics based on the absurdist poetry of Hugo Ball, feels like a moment of catharsis, and that's just at the beginning.

"This ain't no party / This ain't no disco / This ain't no fooling around," David Byrne reminds us during "Life During Wartime." "Cities" explores the life of someone who only feels comfortable when surrounded by the anonymity of urban life, while "Air" uncovers a character so miserable that even the simplest task has become unbearable. "Drugs," well, that speaks for itself. Best of all – certainly scariest of all – might be "Memories Can't Wait," a swirling column of after-party rage and disassociative fear.

Listen to Talking Heads Perform 'Heaven'

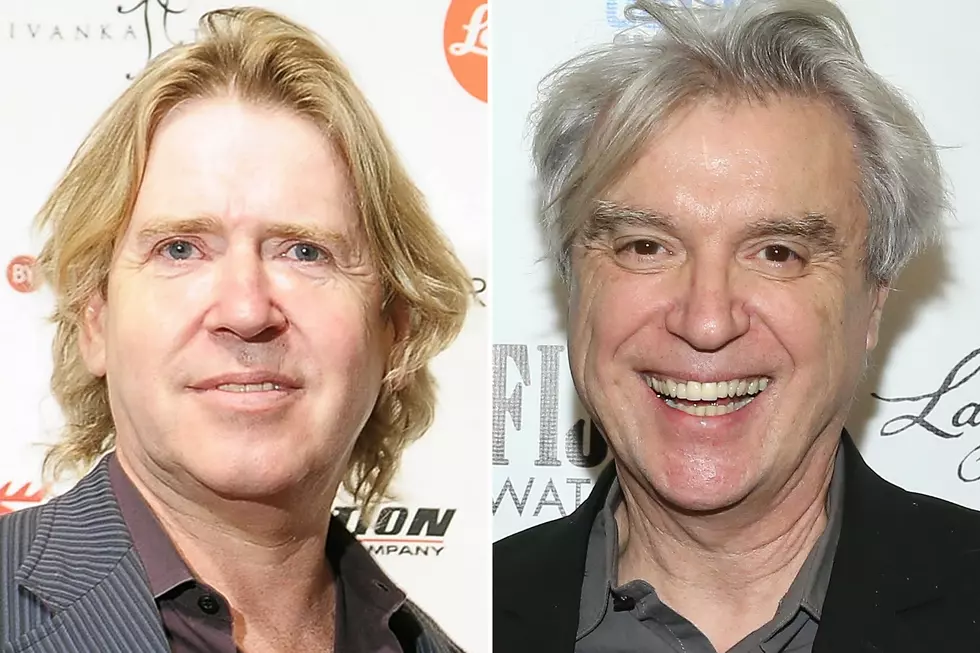

Released on Aug. 3, 1979, Fear of Music "completed the earlier vision of the band, yet had a sophistication about it," underrated multi-instrumentalist Jerry Harrison told Anil Prasad in 1999.

As such, Fear of Music, though it went to No. 21 on the Billboard albums chart, can perhaps be difficult to connect with. Lester Bangs memorably suggested that the album be retitled Fear of Everything. Even the famously cranky Robert Christgau was moved to admit that "a little sweetening might help."

And yet, initially at least, this dystopian vision emerged from a close-knit place, something that might be hard to believe as the candidly depressed Fear of Music unfolds. The album, in fact, began with cords snaking into a loft owned by drummer Chris Frantz and bassist Tina Weymouth from a recording van parked outside.

It couldn't have been more lo-fi, more garage band, more familial. After two albums, and their first breakout hit in a modern cover of Al Green's "Take Me to the River," Talking Heads had decided to return to the punk era's seminal approach.

As the sessions continued, Byrne began to take a more central role. His friend Brian Eno, in the midst of a three-album run as producer, was eventually brought in to help shape the sounds they were creating. By then, Talking Heads had already decided that the anxiety they'd poked fun at before was worth exploring more completely.

Listen to Talking Heads Perform 'Life During Wartime'

And explore it, they did. "We made sure no song sounded exactly like the other," Byrne wrote in his 2012 book How Music Works.

He dubbed the working process in the loft as "incomplete recording," something Byrne was only just beginning to develop. The band would lay down basic tracks, then embellish from there while Byrne improvised lyrics on the spot. Harrison designed the album cover, and suggested the title – an idea that seemed to fit in with the project's overarching theme of displacement.

"We were an alternative to a lot of the overblown pop music that was around then," Byrne told Time years later. "But it wasn't as simple as what I described. The music had this disturbing hue to it."

What they ended up with might be best described – to borrow a Christgau phrase from elsewhere in his original review – as "gritty weirdness." Fear of Music sounds robotic, but intense. Futuristic, yet earthy. Bold but, yeah, afraid. Mikal Gilmore, writing in Rolling Stone in 1979, described it as an "agitated presence in a composed environment." In this way, it works in perfect concert with Byrne's lyrical constructions.

Go back to "Memories Can't Wait," with its insomniac vibe. The song is both unspeakably tired and completely keyed up. That sums up the twilit jitters that envelop Fear of Music, a project that simply bristles with outsider experimentation, hooky invention and rhythmic surprises – even as the lyric sheet travels down these harrowing back alleys.

Listen to Talking Heads Perform 'I Zimbra'

"In the Talking Heads, the rhythm section is like a ship or train – very forceful and certain of where it’s going," Eno told Gilmore. "On top of that, you have this hesitant, doubting quality that dizzily asks, ‘Where are we going?’ That makes for a sense of genuine disorientation, unlike the surface insanity of the more commonplace, expressionist punk groups."

Not everything on the album reaches for that kind of outsized greatness. But the best moments on Fear of Music remain some of the most important things – and, at the same time, some of the darkest – that Talking Heads have ever done. Certainly, as Harrison has noted, the disco paranoia of "I Zimbra" set the course for everything that would follow musically.

There was one more thing: When Fear of Music was first issued, every song was attributed to Byrne, despite the clear involvement of the others. Later editions rectified that, as "Life During Wartime" was properly credited to all four members, Harrison's contributions were noted on "Memories Cant Wait" and "Heaven," and Eno earned a co-writing nod on "Drugs." But the seeds were sewn for divisions that would eventually rip the band apart into the '80s.

In the end, as author Jonathan Lethem has said, this can be viewed as the final Talking Heads album, or the final real one, anyway. After Fear of Music, Byrne began radically expanding the group beyond its founding foursome – both onstage and in the studio – with an eye toward achieving more and more complexities of sound.

By the time the follow-up Remain in Light appeared – with a credit that read "All songs by David Byrne, Brian Eno, Talking Heads" – their era of work as a cooperative quartet was effectively over. The sense of separation so skillfully delineated throughout Fear of Music had been made real.

Top 100 Live Albums

More From KYBB-FM / B102.7